Scikit-learn’s pipelines provide a useful layer of abstraction for building complex estimators or classification models. Its purpose is to aggregate a number of data transformation steps, and a model operating on the result of these transformations, into a single object that can then be used in place of a simple estimator. This allows for the one-off definition of complex pipelines that can be re-used, for example, in cross-validation functions, grid-searches, learning curves and so on. I will illustrate their use, and some pitfalls, in the context of a kaggle text-classification challenge.

The challenge

The goal in the StumbleUpon Evergreen classification challenge is the prediction of whether a given web page is relevant for a short period of time only (ephemeral) or can be recommended still a long time after initial discovery (evergreen).

Each webpage in the provided dataset is represented by its html content as well as additional meta-data, the latter of which I will ignore here for simplicity. Instead I will focus on the use of pipelines to 1) transform text data into a numerical form appropriate for machine learning purposes, and 2) for creating ensembles of different classifiers to (hopefully) improve prediction accuracy (or at least its variance).

Text transformation

A useful tool for the representation of text in a machine learning context is the so-called tf-idf transformation, short for “term frequency–inverse document frequency”. The idea is simple. Each word in a document is represented by a number that is proportional to its frequency in the document, and inversely proportional to the number of documents in which it occurs. Very common words, such as “a” or “the”, thereby receive heavily discounted tf-df scores, in contrast to words that are very specific to the document in question. Scikit-learn provides a TfidfVectorizer class, which implements this transformation, along with a few other text-processing options, such as removing the most common words in the given language (stop words). The result is a matrix with one row per document and as many columns as there are different words in the dataset (corpus).

Pipelines

In few cases, however, is the vectorization of text into numerical values as simple as applying tf-idf to the raw data. Often, the relevant text to be converted needs to be extracted first. Also, the tf-idf transformation will usually result in matrices too large to be used with certain machine learning algorithms. Hence dimensionality reduction techniques are often applied too. Manually implementing these steps everytime text needs to be transformed quickly becomes repetitive and tedious. It needs to be done for the training as well as test set. Ideally, when using cross-validation to assess one’s model, the transformation needs to be applied separately in each fold, particularly when feature selection (dimensionality reduction) is involved. If care is not taken, information about the whole dataset otherwise leaks into supposedly independent evaluations of individual folds.

Pipelines help reduce this repetition. What follows is an example of a typical vectorization pipeline:

def get_vec_pipe(num_comp=0, reducer='svd'):

''' Create text vectorization pipeline with optional dimensionality reduction. '''

tfv = TfidfVectorizer(

min_df=6, max_features=None, strip_accents='unicode',

analyzer="word", token_pattern=r'\w{1,}', ngram_range=(1, 2),

use_idf=1, smooth_idf=1, sublinear_tf=1)

# Vectorizer

vec_pipe = [

('col_extr', JsonFields(0, ['title', 'body', 'url'])),

('squash', Squash()),

('vec', tfv)

]

# Reduce dimensions of tfidf

if num_comp > 0:

if reducer == 'svd':

vec_pipe.append(('dim_red', TruncatedSVD(num_comp)))

elif reducer == 'kbest':

vec_pipe.append(('dim_red', SelectKBest(chi2, k=num_comp)))

elif reducer == 'percentile':

vec_pipe.append(('dim_red', SelectPercentile(f_classif, percentile=num_comp)))

vec_pipe.append(('norm', Normalizer()))

return Pipeline(vec_pipe)

Here, we first create an instance of the tf-idf vectorizer (for its parameters see documentation). We then create a list of tuples, each of which represents a data transformation step and its name (the latter of which is required, e.g., for identifying individual transformer parameters in a grid search). The first two are custom transformers and the last one our vectorizer. The first transformer (“JsonFields”), for example, extracts a particular column from the dataset, in this case the first (0-indexed), interprets its content as json-encoded text, and extracts the json fields with the keys ‘title’, ‘body’ and ‘url’. The corresponding values are concatenated into a single string per row in the dataset. The result is a new transformed dataset with a single column containing the extracted text, which can then be processed by the vectorizer. After the vectorization step, an optional dimensionality reduction is added to the list of transformations before the final pipeline is constructed and returned.

Transformers

Custom transformers such as those above are easily created by subclassing from scikit’s TransformerMixin. This base class exposes a single fit_transform() function, which in turn calls (to be implemented) fit() and transform() functions. For transformers that do not require fitting (no internal parameters to be selected based on the dataset), we can create a simpler base class that only needs the transform function to be implemented:

class Transformer(TransformerMixin):

''' Base class for pure transformers that don't need a fit method '''

def fit(self, X, y=None, **fit_params):

return self

def transform(self, X, **transform_params):

return X

def get_params(self, deep=True):

return dict()

With this in place, the JsonFields transformer looks like this:

class JsonFields(Transformer):

''' Extract json encoded fields from a numpy array. Returns (iterable) numpy array so it can be used as input to e.g. Tdidf '''

def __init__(self, column, fields=[], join=True):

self.column = column

self.fields = fields

self.join = join

def get_params(self, deep=True):

return dict(column=self.column, fields=self.fields, join=self.join)

def transform(self, X, **transform_params):

col = Select(self.column, to_np=True).transform(X)

res = np.vectorize(extract_json, excluded=['fields'])(col, fields=self.fields)

return res

JsonFields itself encapsulates another custom transformer (Select), used here to keep the specification of pipelines concise. It could also have been used as a prior step in the definition of the pipeline. The Select transformer does nothing other than extracting a number of specified columns from a dataset:

class Select(Transformer):

''' Extract specified columns from a pandas df or numpy array '''

def __init__(self, columns=0, to_np=True):

self.columns = columns

self.to_np = to_np

def get_params(self, deep=True):

return dict(columns=self.columns, to_np=self.to_np)

def transform(self, X, **transform_params):

if isinstance(X, pd.DataFrame):

allint = isinstance(self.columns, int) or

(isinstance(self.columns, list) and

all([isinstance(x, int) for x in self.columns]))

if allint:

res = X.ix[:, self.columns]

elif all([isinstance(x, str) for x in self.columns]):

res = X[self.columns]

else:

print "Select error: mixed or wrong column type."

res = X

# to numpy ?

if self.to_np:

res = unsquash(res.values)

else:

res = unsquash(X[:, self.columns])

return res

This transformer is slightly more complicated than strictly necessary as it allows for selection of columns by index or name in the case of a pandas DataFrame.

You may have noticed the use of the function unsquash() and the Transformer Squash in the first definition of the pipeline. This is an unfortunate but apparently required part of dealing with numpy arrays in scikit-learn. The problem is this. One may want, as part of the transform pipeline, to concatenate features from different sources into a single feature matrix. One may do this using numpy’s hstack function or scikit’s built-in FeatureUnion class. However, both only operate on feature columns of dimensionality (n,1). So, for this purpose custom transformers should always return single-column “2-dimensional” arrays or matrices. Scikit’s TfidfVectorizer, on the other hand, only operates on arrays of dimensionality (n,), i.e. on truly one-dimensional arrays (and probably pandas Series). As a result, when working with multiple feature sources, one of them being vectorized text, it is necessary to convert back and forth between the two ways of representing a feature column. For example by using

np.squeeze(np.asarray(X))

for conversion from (n,1) to (n,) or

np.asarray(X).reshape((len(X), 1))

for the other direction. The Squash (and Unsquash) class used above simply wraps this functionality for use in pipelines. For these and some other Transformers you may find useful check here.

Ensembles

The last step in a Pipeline is usually an estimator or classifier (unless the pipeline is only used for data transformation). However, a simple extension allows for much more complex ensembles of models to be used for classification. One way to do this flexibly is to first create a FeatureUnion of different models, in which the predictions of individual models are treated as new features and concatenated into a new feature matrix (one column per predictor). An ensemble prediction can then be made simply by averaging the predictions (or using a majority vote), or by using the predictions as inputs to a final predictor, for example.

For the creation of a FeatureUnion of models, we require the individual models to return their predictions in their transform calls (since the fitting of a Pipeline only calls the fit and transform functions for all but the last step, but not the predict function). We hence need to turn a predictor into a transformer, wich can be done using a wrapper such as this:

class ModelTransformer(TransformerMixin):

''' Use model predictions as transformed data. '''

def __init__(self, model, probs=True):

self.model = model

self.probs = probs

def get_params(self, deep=True):

return dict(model=self.model, probs=self.probs)

def fit(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.model.fit(*args, **kwargs)

return self

def transform(self, X, **transform_params):

if self.probs:

Xtrf = self.model.predict_proba(X)[:, 1]

else:

Xtrf = self.model.predict(X)

return unsquash(Xtrf)

With this in place we may build a FeatureUnion-based ensemble like this:

def build_ensemble(model_list, estimator=None):

''' Build an ensemble as a FeatureUnion of ModelTransformers and a final estimator using their

predictions as input. '''

models = []

for i, model in enumerate(model_list):

models.append(('model_transform'+str(i), ModelTransformer(model)))

if not estimator:

return FeatureUnion(models)

else:

return Pipeline([

('features', FeatureUnion(models)),

('estimator', estimator)

])

We are now in a position to create a rather complex text-classification pipeline. For example, one pipeline I’ve built for the kaggle competition trains a logistic regression on the result of the tf-idf vectorization, then combines the prediction with those from three different models trained on a dimensionality-reduced form of the tf-idf:

def get_custom_pipe(num_comp=0, clf=None):

''' Create complex text vectorization pipeline. '''

# Get non-dim-reduced vectorizer

pipe = get_vec_pipe(num_comp=0)

# Add a logit on non-reduced tfidf, and ensemble on reduced tfidf

clfs = ['rf', 'sgd', 'gbc']

pipe.steps.append(

('union', FeatureUnion([

('logit', ModelTransformer(build_classifier('logit'))),

('featpipe', Pipeline([

('svd', TruncatedSVD(num_comp)),

('svd_norm', Normalizer(copy=False)),

('red_featunion', build_ensemble([build_classifier(name) for name in clfs]))

]))

]))

)

if clf:

pipe.steps.append(('ensemblifier', clf))

return pipe

This function takes as input the final classifier that should be trained on the component predictions. One may, for example, use a built-in classifier (say another logistic regression), in which case one ends up with a stacked ensemble. Or one may simply average or take the majority vote of the individual prediction, in which case one is simply creating a kind of combiner. For the latter there is no built-in class in scikit-learn, but one can easily be created:

class EnsembleBinaryClassifier(BaseEstimator, ClassifierMixin, TransformerMixin):

''' Average or majority-vote several different classifiers. Assumes input is a matrix of individual predictions, such as the output of a FeatureUnion of ModelTransformers [n_samples, n_predictors]. Also see http://sebastianraschka.com/Articles/2014_ensemble_classifier.html.'''

def __init__(self, mode, weights=None):

self.mode = mode

self.weights = weights

def fit(self, X, y=None):

return self

def predict_proba(self, X):

''' Predict (weighted) probabilities '''

probs = np.average(X, axis=1, weights=self.weights)

return np.column_stack((1-probs, probs))

def predict(self, X):

''' Predict class labels. '''

if self.mode == 'average':

return binarize(self.predict_proba(X)[:,[1]], 0.5)

else:

res = binarize(X, 0.5)

return np.apply_along_axis(lambda x: np.bincount(x.astype(int), self.weights).argmax(), axis=1, arr=res)

For prediction of class probabilities this model simply returns a (possibly weighted) average of individual predictions. For compatibility with some of scikit-learn’s built-in functionality I return the probabilities both for negative and positive classes (scikit expects the latter in the second column). For the prediction of class labels, the model either uses a thresholded version of the averaged probabilities, or a majority vote directly on thresholded individual predictions (it may be useful to allow for specification of the threshold as well). In either case, the hope is that the combined predictions of several classifiers will reduce the variance in prediction accuracy when compared to a single model only. Supplying an instance of this class to the above get_custom_pipe() function completes our relatively complex pipeline.

Use of Pipelines

Though requiring some additional work in the beginning to wrap custom data transformations in their own classes, once a pipeline has been defined, it can be used anywhere in scikit-learn in place of a simple estimator or classifier.

For example, estimating the performance of the pipeline using cross-validation on training data is as simple as

scores = cross_validation.cross_val_score(pipeline, X, y, cv=10, scoring='roc_auc')

One advantage is that this applies all data transformations (including any feature selection steps) independently on each fold, without leaking information from the whole dataset. Note though, that there are kinds of data mangling or preprocessing that are better done once for the whole set.

Equally easily predictions are created on new data:

y_pred = pipeline.predict_proba(X_new)[:,1]

And here is a grid search to automatically determine the best parameters of models used in the pipeline (using cross-validation internally):

gs = GridSearchCV(pipeline, grid, scoring='roc_auc', cv=10)

Here the only subtelty involves specification of the parameter grid (the parameter values to be tested). Since our pipelines can form a complex hierarchy, the parameter names of individual models need to refer to the name of the model in the pipeline. For example, if the pipeline contains a logistic regression step, named ‘logit’, then the values to be tested for the model’s ‘C’ parameter need to be supplied as

grid = {'logit__C' : (0.1, 1, 5, 10)}

i.e. using the model name followed by a double underscore followed by the parameter name.

Conclusion

I hope there is some useful information here. For the code I used to predict StumbleUpon pages see here on github. Somewhat disappointingly though, the complex pipeline in this case doesn’t perform significantly better than a simple tf-idf followed by logistic regression (without the ensemble). This may be due to the small size of the data set, the fact that the different models in the ensemble all fail in similar ways, or a range of other reasons. In any case, also check Zac Stewart’s blog post for another introduction to Pipelines. And in a follow-up post I will show some ways of analysing the results of a tf-idf in scikit-learn.

Afterword

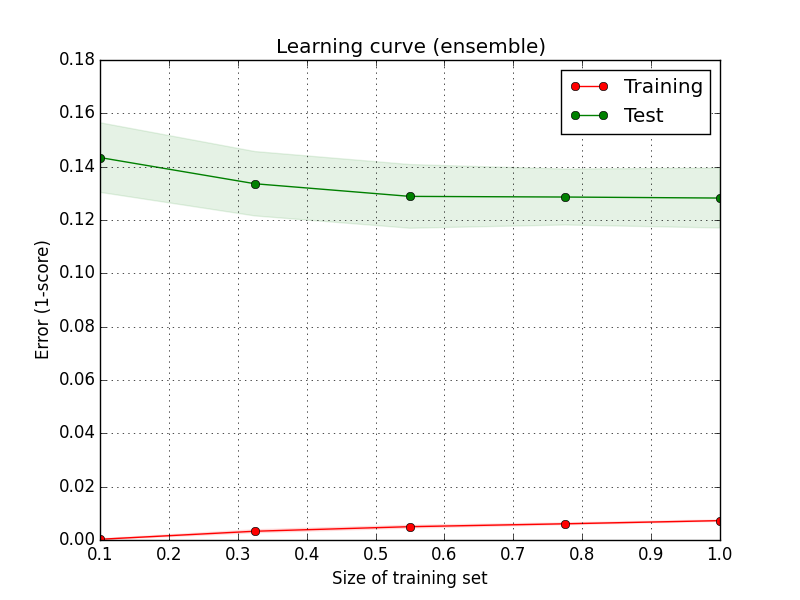

As mentioned in the beginning a Pipeline instance may also be used with scikit-learn’s validation and learning curve. Here is the learning curve for the above pipeline:

The complex pipeline is certainly not suffering from high bias, as that would imply a higher error on the training set. From the gap between training and test error it rather seems like the model may exhibit too much variance, i.e. overfitting on the training folds. This makes sense both because our model is rather complex, and also because the size of the whole training data is relatively small (less than 8000 documents, compare that to the number of features produced by the tf-df, which can run into several tens of thousands without dimensionality reduction). Collection of more data would thus be one way to try and improve performance here (and it might also be useful to investigate different forms of regularization to avoid overfitting. Interestingly though, grid-search of the logistic regression led to best results without regularization). On the other hand, test error does not seem to be decreasing much with increasing size of the training set, indicating perhaps some inherent unpredictability in the data (some comments in the forum e.g. indicate that the class labels seem to have been assigned somewhat inconsistently).